Secular usage of the church is big business. I use the term “secular” loosely but bear with me. Think Norwich Cathedral’s giant indoor helter-skelter, or the first main-branch church post office at St James’s in West Hampstead, and there’s a few wine bars and crèches thrown in the mix there.

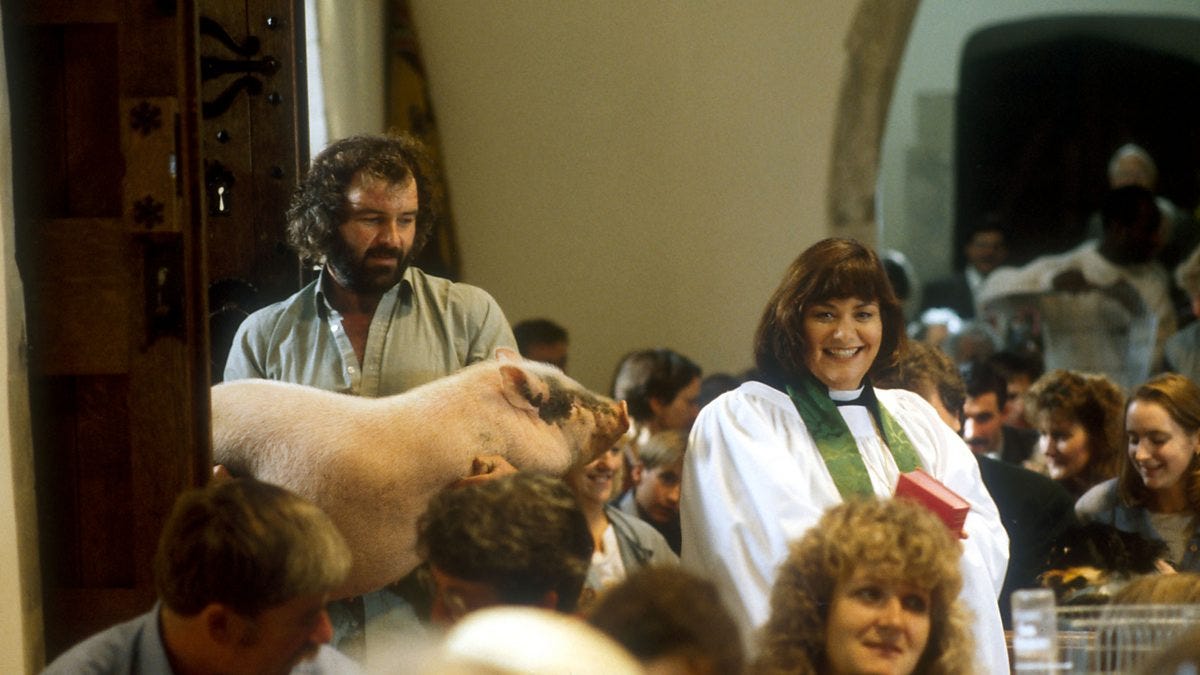

No doubt, too, the popularity of Geraldine’s animal service in the Vicar of Dibley and the harmless religious mockery running throughout Father Ted, has aided the debate over the so-called increasing “secularisation” of the church.

Fierce controversy continues to surround these attempts at a new rethinking of the Church’s sales pitch—with much of the debate lamented over the suggestion that the church should be about liturgy and that alone, so follows its traditional usage through history. But let’s organise the facts from the fallacies—and then see where the dichotomy really lies. Let’s unpick the motivations behind this seemingly endless fascination with how our church buildings are used…and discover how our four-legged friends have been a continued presence of worship throughout history.

Take a look at the two images below:

Note the frivolity apparent within these sacred spaces. Note the dogs and children running though the nave—no doubt a portrayal of an early and broad inculcation to the faith.

Of course, both are depictions of a post-medieval church. So, what about this one from the fifteenth century:

What we are seeing here are a variety of practices we would perhaps find quite horrifying if we saw them occurring in the naves of our own churches today. And yet the artworks here are, we could argue, rather idealised portrayals of the historic church interior. Therefore, what actually went down within these most holy walls was far more interesting, and indeed, at times, rather surprising.

‘One of the most, if not the most, vital debates in which theologians are engaged at the present day is that which concerns the secular nature of Christianity’. This quote from J.G. Davies was first written in 1968. However, it is perhaps just, if not more, relevant to the church of 2022. He goes on to opine, ‘for over a Millennium and a half churches were the scene of a host of varied secular activities; To ignore them is to pass over an essential element in understanding them functionally’.

And my trivial reference to Dibley's animal service was to inject a little bit of humour, of course, but it did have some grain of historical truth to it. In fact, a variety of pets were commonly brought into church. The fourteenth-century publication entitled Le Menagier de Paris (The Goodman of Paris) actually advised his wife to carry her hawk whenever within a crowd, even ‘at church’, while ladies with small lapdogs were a most common sight.

Of course, though a common pet of religious orders, the dogs did not always heed their owners’ commands. At St Mary's in Winchester, the Bishop William of Wyekham recorded in 1387 how many nuns would bring a variety of animals into the church, which proceeded to hinder and interrupt the services, and meant the nuns paid more attention to their pets than the holy offices—as he laments, to the grievous peril of their souls! Almost a century earlier, Archbishop of York, William Greenfield, had also protested about the presence of small dogs in the choir, as they were found to ‘impede the service and hinder the devotion of the nuns’.

A fifteenth-century monastic regulation against dogs and puppies also told how ‘oftentimes [they would] trouble the service by their barkings, and sometimes tear the church books’. The Visitation reports and churchwardens’ accounts of several churches thus recall how many parishes had to employ special dog whippers in order to keep out the nuisance hounds and due to transgressions against bringing pets into the church—though some were, of course, specifically allowed inside for keeping children, other animals, or any unruly persons, outside the sacred precincts.

Official ecclesiastical dog whippers were equipped with a three-foot-long whip and a pair of tongs used to remove the bothersome animals. A dog whipper's whip survives in the parish church of St Anne at Baslow in Derbyshire and a dog whipper's pew is still preserved in St Margaret's Church in Wrenbury, Cheshire—and Saint Margaret’s at Westminster also paid a ‘dog wyper’ as late as 1503-04. A notable carving of a dog whipper removing a dog with his whip can also be seen in the Great Church of St Bavo in Haarlem, Netherlands.

One of the last recorded dog whippers was John Pickard, who was appointed to Exeter Cathedral in 1856. A small room in the cathedral is still known as the Dog Whipper's Flat. From this elevated position, the dog-whipper could watch things going on inside the nave and spot any feral dogs who might be loose inside the church.

Though canon law never officially forbade animals entering churches, the practice appeared to die out in the first half of the twentieth century, concurrent with when church attendance as a whole also decreased—but, to this day, a few quiet pooches can still be found laid between the feet of worshippers.

Until next time, don't forget: always remember to look up!

E :)

Dogs or animals in churches : no, no , no , no yes ! 😊

Wow, what a fascinating "tail" (!) 😂 Thank you so, so much (!) for this, Emma! 🤗

So, I am always very eager to learn life lessons from good stories. And this article is no different. 🤗 In want of such lessons, I would like to read this article in recognition of the distinction people often make between the methodology of most different case study and the most similar case study, choosing the former. This exercise would be much, much less ambitious and grand than that attempted by a famous historian, Helen Castor, in her 2010 book, "She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled Before Elizabeth I" (the aim of which, as far as I can tell, is to show that, although those women lived in very different times, the outcome of them becoming queen and the prominent presence of patriarchy were the same), and this choice is without much solid justifications either, I admit, but I just want to assume that every difference other than the struggles of the church against ever changing society (e.g. how to convert pagan England to what to do with increasing secularism) in which it is deeply situated and the presence of dogs (which must surely be false but I have limited info so... :D) here for drawing out the said life lessons.

In this connection, I am thinking it might be okay (?) to make a distinction between the past or pre-increasing secularisation of the church including the medieval period and the present, quickly increasing secularisation of the church (of course it would probably have been a gradual process this - maybe linked to the increasing modernisation of Western society? - not sure...). Emma's tale however made it clear that the presence of dogs and sometimes even other animals have been a constant presence in the church regardless of this distinction yet, in the present, the number and frequency of dogs in churches are historically speaking markedly reduced, and the dog's presence in churches is also today too often limited to those very quiet and/or well-behaved. And, if indeed the increasing secularisation is the main difference between the past and the present context for accounting the behaviour and presence (or lack thereof) of dogs in churches, then I would like to venture to say that secularisation refers to what happens to humans, not animals, so that it is the predominant concerns of the church (e.g., increasing secularisation) that determine what (have had) happens(-ed) to dogs in churches, not the presence or the behaviour of dogs (or some categories of already marginalised humans for that matter - see next sentence) per se. And if I further venture to say that both dogs and humans are God's creation, then I think Emma's article tells us this very important historical insight that the church has always been quite capable of marginalising God's creation (whatever forms it takes) depending only on its, not anyone else's, concerns (e.g., think how gays or female bishops are considered and treated by various churches around the world - as well as, and more relevant to this article, how to bring in more human, not dog/animal, church worshippers in an era of increasing secularisation (I am guessing - or maybe more committed religious people - humans, anyway... :p)).

As the current church searches deep into its people and its soul to battle against (?) increasing secularisation of the church (as well as other social issues, named a couple above) today, then, this Emma's brilliant tale about dogs should be read widely by all church-goers and -crawlers alike as a forever relevant and important warning for the church as it tries to navigate itself through this obviously too earthly a world forward.

Amen! :D